Chunking in Natural Language Processing is simply dividing large bodies of text into smaller pieces that computers can manage more easily. Splitting large datasets into chunks enables your Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) system to embed, index, and store even very large datasets optimally. But how you chunk your data is crucial in determining whether you can efficiently return only the most relevant results to your user queries.

To get your RAG system to handle user queries better, you need a chunking method that's a good fit for your data. Some widely used chunking algorithms are rule-based - e.g., fixed character splitter, recursive character splitter, document-specific splitter, among others. But in some real-world applications, rule-based methods have trouble. If, for example, your dataset has multi-topic documents, rule-based splitting algorithms can result in incomplete contexts or noise-filled chunks. Semantic chunking, on the other hand - because it divides text on the basis of meaning rather than rules - creates chunks that are semantically independent and cohesive, and therefore results in more effective text processing and information retrieval.

But exactly which semantic chunking method should you use? In this article, we'll describe and implement three different popular semantic chunking methods - embedding-similarity-based, hierarchical-clustering-based, and LLM-based. Then we'll evaluate them, applying an embedding model and a reranker to two different datasets - one that tests our chunking methods' ability to handle complex, multi-hop reasoning tasks, and another that checks if they can identify and extract only the most relevant results.

Let's get started.

In semantic chunking, a splitter adaptively picks the breakpoint between sentences by comparing embedding similarity. This ensures that each chunk contains semantically cohesive sentences. Typically, a semantic splitting algorithm uses a sliding window approach, calculating the cosine similarity between the embeddings of consecutive sentences, and establishing a threshold for assigning chunk boundaries. When sentence similarity drops below this threshold, it signals a shift in semantic content, and the splitter marks a breakpoint.

The workflow of a semantic splitter has basically 3 basic steps:

Split the text into sentences.

Generate embeddings for the sentences.

Group sentences based on their embedding similarity.

Which method of semantic chunking will produce optimal outcomes depends on your use case. To get a sense of which splitting algorithms fit which scenarios, let's take an in-depth look at, implement, and evaluate three popular methods: embedding-similarity-based, hierarchical-clustering-based, and LLM-based.

In embedding-similarity-based chunking, we create chunks by comparing semantic similarity between sentences, which we calculate by measuring the cosine distance between consecutive sentence embeddings.

Let's walk through how to implement it.

First, we install and import the required libraries.

import numpy as np from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import cosine_similarity from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import cosine_distances from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModel import torch

We define a helper function to split the text into sentences - based on regular end-of-sentence punctuation followed by a whitespace.

def _split_sentences(text): sentences = re.split(r'(?<=[.?!])\s+', text) return sentences

To provide a context window to better understand each sentence, we define a function to combine it with its preceding and following sentences.

def _combine_sentences(sentences): combined_sentences = [] for i in range(len(sentences)): combined_sentence = sentences[i] if i > 0: combined_sentence = sentences[i-1] + ' ' + combined_sentence if i < len(sentences) - 1: combined_sentence += ' ' + sentences[i+1] combined_sentences.append(combined_sentence) return combined_sentences

Next, we define a cosine similarity distance calculation function, and an embedding function.

def _calculate_cosine_distances(embeddings): distances = [] for i in range(len(embeddings) - 1): similarity = cosine_similarity([embeddings[i]], [embeddings[i + 1]])[0][0] distance = 1 - similarity distances.append(distance) return distances def get_embeddings(texts, model_name="BAAI/bge-small-en-v1.5"): tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name) model = AutoModel.from_pretrained(model_name) encoded_input = tokenizer(texts, padding=True, truncation=True, return_tensors="pt") with torch.no_grad(): model_output = model(**encoded_input) embeddings = mean_pooling(model_output, encoded_input['attention_mask']) return embeddings.numpy() def mean_pooling(model_output, attention_mask): token_embeddings = model_output[0] input_mask_expanded = attention_mask.unsqueeze(-1).expand(token_embeddings.size()).float() return torch.sum(token_embeddings * input_mask_expanded, 1) / torch.clamp(input_mask_expanded.sum(1), min=1e-9)

Now that we've split the text into sentences, calculated similarity, and generated embeddings, we turn to chunking.

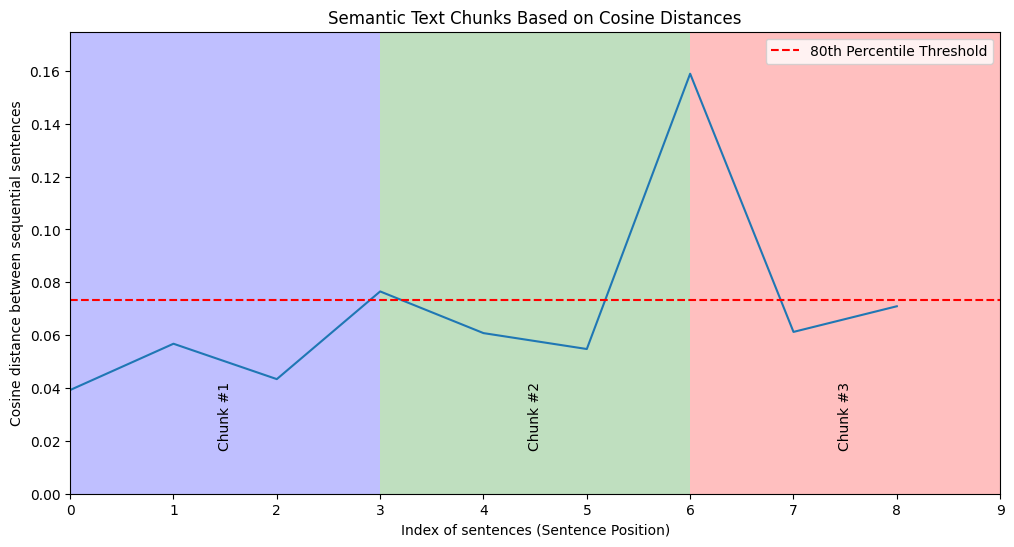

Our chunking function determines a breakpoint_distance_threshold for identifying breakpoints. We use breakpoint_percentile_threshold to identify indices where cosine distances exceed the 80th percentile. Sentences with distances exceeding the threshold are considered chunk boundaries. chunk_text then creates chunks by joining sentences between breakpoints. Any sentences in the text remaining after the last identified breakpoint are clustered into a final chunk.

def chunk_text(text): single_sentences_list = _split_sentences(text) print(single_sentences_list) combined_sentences = _combine_sentences(single_sentences_list) print(combined_sentences) embeddings = get_embeddings(combined_sentences) distances = _calculate_cosine_distances(embeddings) # Determine the threshold distance for identifying breakpoints based on the 80th percentile of all distances. breakpoint_percentile_threshold = 80 breakpoint_distance_threshold = np.percentile(distances, breakpoint_percentile_threshold) # Find all indices where the distance exceeds the calculated threshold, indicating a potential chunk breakpoint. indices_above_thresh = [i for i, distance in enumerate(distances) if distance > breakpoint_distance_threshold] chunks = [] start_index = 0 for index in indices_above_thresh: chunk = ' '.join(single_sentences_list[start_index:index+1]) chunks.append(chunk) start_index = index + 1 # If there are any sentences left after the last breakpoint, add them as the final chunk. if start_index < len(single_sentences_list): chunk = ' '.join(single_sentences_list[start_index:]) chunks.append(chunk) return chunks

Depending on the needs of your use case - e.g., more fine-grained analysis, improved context, enhanced readability, alignment with user queries, etc. - you may also want to reduce your breakpoint distance threshold, generating more chunks.

Let's run a sample text input using our 80% breakpoint_percentile_threshold to see what results we get.

text = """ Regular exercise is essential for maintaining overall health and well-being. It helps in controlling weight, improving cardiovascular health, and boosting mental health. Engaging in physical activity regularly can also enhance the immune system, reduce the risk of chronic diseases, and increase energy levels. Regular workouts are known to improve muscle strength and flexibility, which can prevent injuries and enhance mobility. Moreover, exercise contributes to better sleep and improved mood, which are crucial for daily functioning. Physical activity can also help reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, leading to a more balanced emotional state. Activities like walking, jogging, or swimming can be easily incorporated into a daily routine, making it accessible for everyone. By setting realistic goals and staying consistent, individuals can enjoy these benefits and lead a healthier lifestyle. Group fitness classes or sports teams can provide motivation and social support, making exercise more enjoyable and sustainable. """ chunks = chunk_text(text) for i, chunk in enumerate(chunks, 1): print(f"Chunk {i}:") print(chunk) print("----------------------------------------------------------------------------") print(f"\nTotal number of chunks: {len(chunks)}")

Here's the resulting output:

Chunk 1: Regular exercise is essential for maintaining overall health and well-being. It helps in controlling weight, improving cardiovascular health, and boosting mental health. Engaging in physical activity regularly can also enhance the immune system, reduce the risk of chronic diseases, and increase energy levels. Regular workouts are known to improve muscle strength and flexibility, which can prevent injuries and enhance mobility. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chunk 2: Moreover, exercise contributes to better sleep and improved mood, which are crucial for daily functioning. Physical activity can also help reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, leading to a more balanced emotional state. Activities like walking, jogging, or swimming can be easily incorporated into a daily routine, making it accessible for everyone. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chunk 3: By setting realistic goals and staying consistent, individuals can enjoy these benefits and lead a healthier lifestyle. Group fitness classes or sports teams can provide motivation and social support, making exercise more enjoyable and sustainable. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Our results seem very relevant and discrete. So far so good. Now, let's take a look at our second semantic chunking method.

In this approach, we again calculate semantic similarity in terms of cosine distances between embeddings of consecutive sentences. But this time we hierarchically cluster our sentences. What exactly does this look like?

First, let's import the required libraries. Our utility functions are the same as in embedding-similarity-based chunking, but here we also add utilities for clustering and cluster evaluation.

import numpy as np from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import cosine_similarity from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import cosine_distances from sklearn.metrics import silhouette_score from scipy.cluster.hierarchy import linkage, fcluster from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModel import torch

The chunk_text function in hierarchical clustering calculates a distance matrix based on cosine distances between embeddings - the linkage method builds a hierarchical cluster tree. To determine your chunk boundaries and how closely your sentences will be grouped, you use either a specified number of clusters (num_clusters) or a distance threshold (distance_threshold). The chunk_text function then assigns each sentence to a cluster and returns the resulting clusters as chunks of text.

def chunk_text(text, num_clusters=4, distance_threshold=None): single_sentences_list = _split_sentences(text) print(single_sentences_list) combined_sentences = _combine_sentences(single_sentences_list) print(combined_sentences) embeddings = get_embeddings(combined_sentences) distance_matrix = cosine_distances(embeddings) Z = linkage(distance_matrix, method='average') # 'average' is for average linkage; you can also try 'ward', 'complete', etc. if num_clusters: cluster_labels = fcluster(Z, t=num_clusters, criterion='maxclust') elif distance_threshold: cluster_labels = fcluster(Z, t=distance_threshold, criterion='distance') else: raise ValueError("Either num_clusters or distance_threshold must be specified.") chunks = [] current_chunk = [] current_label = cluster_labels[0] for i, sentence in enumerate(single_sentences_list): if cluster_labels[i] == current_label: current_chunk.append(sentence) else: # Start a new chunk when the cluster label changes chunks.append(' '.join(current_chunk)) current_chunk = [sentence] current_label = cluster_labels[i] # Append the last chunk if current_chunk: chunks.append(' '.join(current_chunk)) return chunks

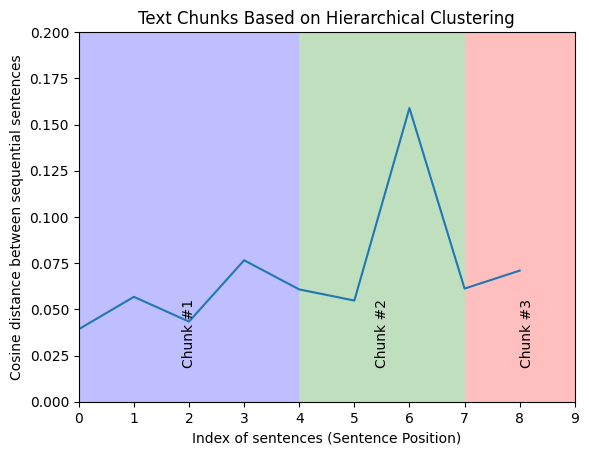

Let's use the same text (as we used with embedding-similarity-based chunking) and, this time, apply hierarchical clustering to it.

text = """ Regular exercise is essential for maintaining overall health and well-being. It helps in controlling weight, improving cardiovascular health, and boosting mental health. Engaging in physical activity regularly can also enhance the immune system, reduce the risk of chronic diseases, and increase energy levels. Regular workouts are known to improve muscle strength and flexibility, which can prevent injuries and enhance mobility. Moreover, exercise contributes to better sleep and improved mood, which are crucial for daily functioning. Physical activity can also help reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, leading to a more balanced emotional state. Activities like walking, jogging, or swimming can be easily incorporated into a daily routine, making it accessible for everyone. By setting realistic goals and staying consistent, individuals can enjoy these benefits and lead a healthier lifestyle. Group fitness classes or sports teams can provide motivation and social support, making exercise more enjoyable and sustainable. """ chunks = chunk_text(text) for chunk in chunks: print(chunk,"\n----------------------------------------------------------------------------\n") print(f"\n{len(chunks)} chunks")

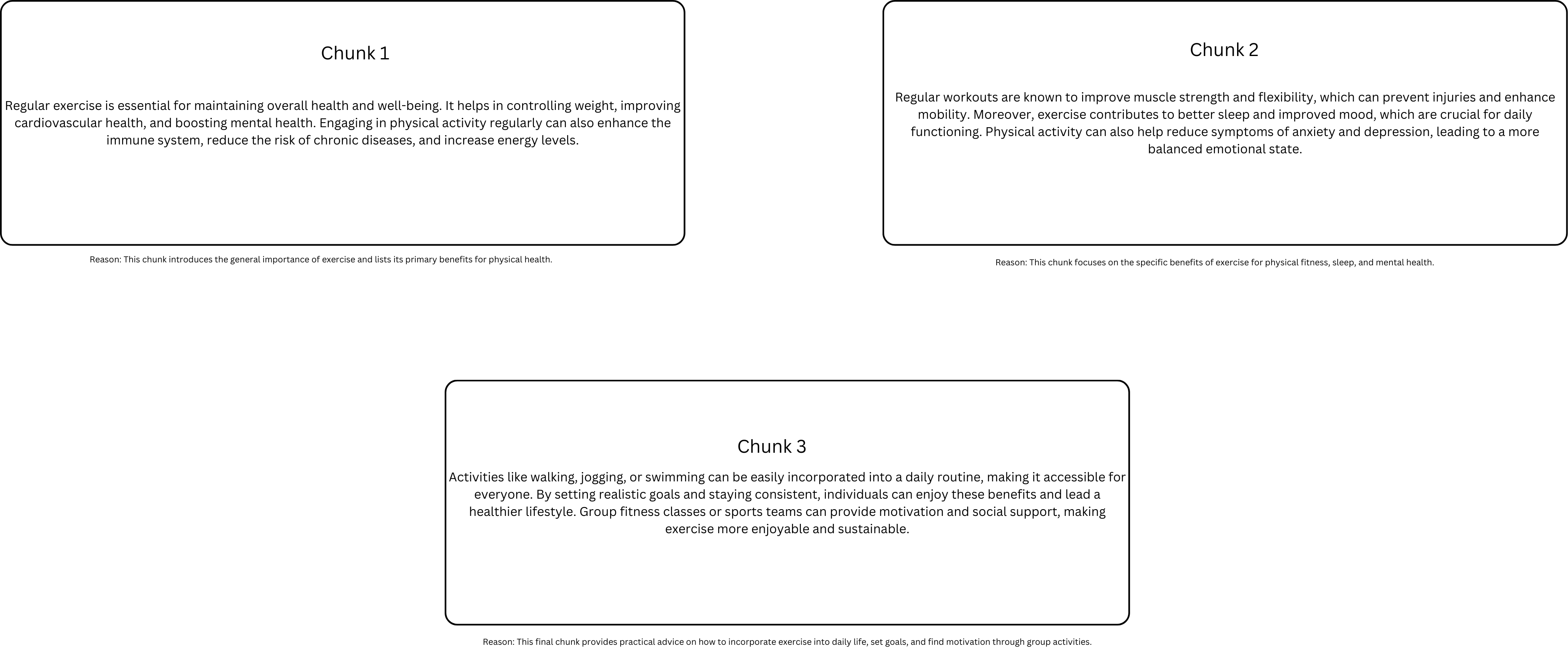

Here's our output:

Chunk 1: Regular exercise is essential for maintaining overall health and well-being. It helps in controlling weight, improving cardiovascular health, and boosting mental health. Engaging in physical activity regularly can also enhance the immune system, reduce the risk of chronic diseases, and increase energy levels. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chunk 2: Regular workouts are known to improve muscle strength and flexibility, which can prevent injuries and enhance mobility. Moreover, exercise contributes to better sleep and improved mood, which are crucial for daily functioning. Physical activity can also help reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, leading to a more balanced emotional state. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chunk 3: Activities like walking, jogging, or swimming can be easily incorporated into a daily routine, making it accessible for everyone. By setting realistic goals and staying consistent, individuals can enjoy these benefits and lead a healthier lifestyle. Group fitness classes or sports teams can provide motivation and social support, making exercise more enjoyable and sustainable. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------

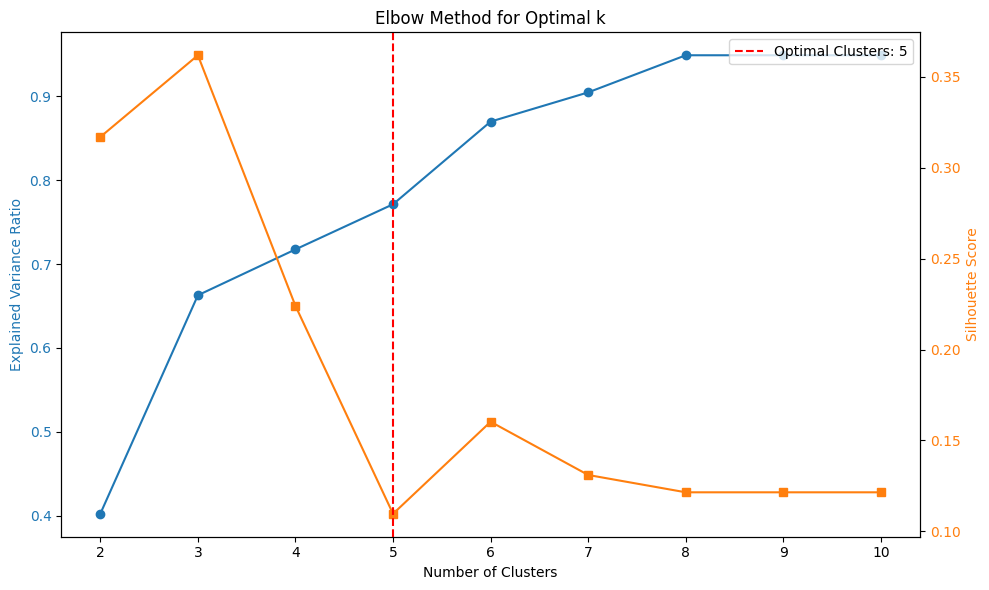

These results look pretty decent. But to make our clusters even more optimized (meaningfully tight and internally cohesive), we can incorporate Within-Cluster Sum of Squares (WCSS) - a measure of the cluster compactness. WCSS calculates the sum of the squared distances between each point in a cluster and the cluster's centroid. The lower the WCSS, the more compact and tightly-knit are the clusters - i.e., sentences within each chunk are more semantically similar. The elbow point is a heuristic method for determining the optimal number of clusters - the point at which adding more clusters doesn't significantly reduce the WCSS.

Let's try adding WCSS and the elbow point method to see how it affects our results.

from sklearn.metrics import silhouette_score def determine_optimal_clusters(embeddings, max_clusters=10): distance_matrix = cosine_distances(embeddings) Z = linkage(distance_matrix, method='average') wcss = [] for n_clusters in range(2, max_clusters + 1): cluster_labels = fcluster(Z, t=n_clusters, criterion='maxclust') wcss.append(calculate_wcss(embeddings, cluster_labels)) total_variance = np.sum((embeddings - np.mean(embeddings, axis=0))**2) explained_variance = [1 - (w / total_variance) for w in wcss] optimal_clusters = find_elbow_point(range(2, max_clusters + 1), explained_variance) return optimal_clusters def calculate_wcss(data, labels): n_clusters = len(set(labels)) wcss = 0 for i in range(n_clusters): cluster_points = data[labels == i+1] cluster_mean = np.mean(cluster_points, axis=0) wcss += np.sum((cluster_points - cluster_mean)**2) return wcss def find_elbow_point(x, y): diffs = np.diff(y, 2) return x[np.argmax(diffs) + 1] def chunk_text_with_clusters(text, num_clusters): single_sentences_list = _split_sentences(text) combined_sentences = _combine_sentences(single_sentences_list) embeddings = get_embeddings(combined_sentences) distance_matrix = cosine_distances(embeddings) Z = linkage(distance_matrix, method='average') cluster_labels = fcluster(Z, t=num_clusters, criterion='maxclust') chunks = [] current_chunk = [] current_label = cluster_labels[0] for i, sentence in enumerate(single_sentences_list): if cluster_labels[i] == current_label: current_chunk.append(sentence) else: chunks.append(' '.join(current_chunk)) current_chunk = [sentence] current_label = cluster_labels[i] if current_chunk: chunks.append(' '.join(current_chunk)) return chunks def chunk_text(text, max_clusters=10): single_sentences_list = _split_sentences(text) combined_sentences = _combine_sentences(single_sentences_list) embeddings = get_embeddings(combined_sentences) optimal_clusters = determine_optimal_clusters(embeddings, max_clusters) return chunk_text_with_clusters(text, num_clusters=optimal_clusters)

You can adjust the value of max_clusters - more for longer text input, less for shorter.

What insights does applying the WCSS elbow method give us? Let's take a look.

The elbow point (vertical red line, at 5 clusters) is where the rate of decrease sharply shifts.

The silhouette score (right axis) is a measure of both how similar an embedding is to its cluster and how different it is from other clusters' embeddings. A high silhouette score indicates that our clustering is optimal; a low score may suggest that we should reconsider the number of clusters.

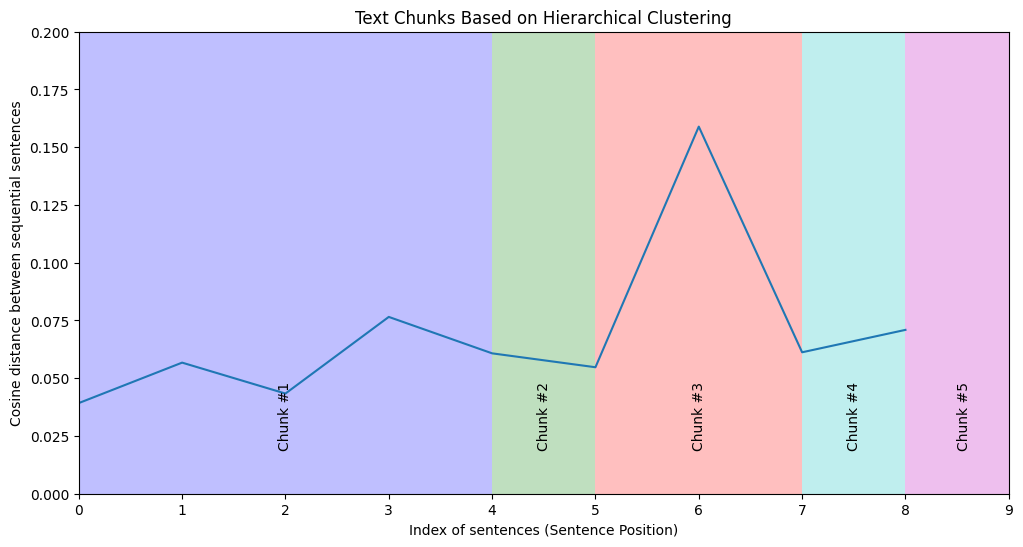

What are our WCSS outputs? We have 5 chunks that, based on our elbow point, should give us the most internally similar and externally distinct clusters.

Chunk 1: Regular exercise is essential for maintaining overall health and well-being. It helps in controlling weight, improving cardiovascular health, and boosting mental health. Engaging in physical activity regularly can also enhance the immune system, reduce the risk of chronic diseases, and increase energy levels. Regular workouts are known to improve muscle strength and flexibility, which can prevent injuries and enhance mobility. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chunk 2: Moreover, exercise contributes to better sleep and improved mood, which are crucial for daily functioning. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chunk 3: Physical activity can also help reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, leading to a more balanced emotional state. Activities like walking, jogging, or swimming can be easily incorporated into a daily routine, making it accessible for everyone. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chunk 4: By setting realistic goals and staying consistent, individuals can enjoy these benefits and lead a healthier lifestyle. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chunk 5: Group fitness classes or sports teams can provide motivation and social support, making exercise more enjoyable and sustainable.

Now that we've looked at our first two semantic chunking methods (semantic embedding and hierarchical clustering), let's turn to consider our third semantic chunking method.

In LLM-based chunking, you prompt a large language model to process your text, convert it into semantic embeddings, evaluate them, and determine logical breakpoints for creating chunks. Here, our prompting aims to identify propositions - highly refined chunks that are semantically rich and self-contained, preserving context and meaning - thereby improving retrieval in downstream applications.

Here is the complete code, implemented with a base class from LangChain:

from langchain.text_splitter import TextSplitter from typing import List import uuid from langchain_huggingface import HuggingFacePipeline from langchain import PromptTemplate from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModelForCausalLM, pipeline, BitsAndBytesConfig, AutoModel from langchain_community.llms import HuggingFaceHub from langchain.chains import create_extraction_chain_pydantic from pydantic import BaseModel from langchain_core.prompts import ChatPromptTemplate from typing import List from langchain.docstore.document import Document from langchain.output_parsers import PydanticOutputParser import json from pydantic import ValidationError import re import dspy import time class ExtractSentences(dspy.Signature): """Extract meaningful propositions (semantic chunks) from the given text.""" text = dspy.InputField() sentences = dspy.OutputField(desc="List of extracted sentences") class ExtractSentencesProgram(dspy.Program): def run(self, text): extract = dspy.Predict(ExtractSentences) result = extract(text=text) return result.sentences class LlmSemanticChunker(TextSplitter): def __init__(self, llm, chunk_size: int = 1000): super().__init__(chunk_size=chunk_size) self.llm = llm self.chunk_size = chunk_size # Explicitly set chunk_size as an instance attribute dspy.settings.configure(lm=llm) self.extractor = ExtractSentencesProgram() def get_propositions(self, text): sentences = self.extractor.run(text) if isinstance(sentences, list): return sentences # Fallback: extract sentences heuristically return [s.strip() for s in text.split('.') if s.strip()] def split_text(self, text: str) -> List[str]: """Extract propositions and chunk them accordingly.""" propositions = self.get_propositions(text) return self._chunk_propositions(propositions) def split_documents(self, documents: List[Document]) -> List[Document]: """Split documents into chunks.""" split_docs = [] for doc in documents: chunks = self.split_text(doc.page_content) for i, chunk in enumerate(chunks): metadata = doc.metadata.copy() metadata.update({"chunk_index": i}) split_docs.append(Document(page_content=chunk, metadata=metadata)) return split_docs def _chunk_propositions(self, propositions: List[str]) -> List[str]: chunks = [] current_chunk = [] current_size = 0 for prop in propositions: prop_size = len(prop) if current_size + prop_size > self.chunk_size and current_chunk: chunks.append(" ".join(current_chunk)) current_chunk = [] current_size = 0 current_chunk.append(prop) current_size += prop_size if current_chunk: chunks.append(" ".join(current_chunk)) return chunks

Let's see what output we get from LLM-based chunking using the same input as we used in our two methods above.

Chunk 1: Regular exercise is essential for maintaining overall health and well-being It helps in controlling weight, improving cardiovascular health, and boosting mental health Engaging in physical activity regularly can also enhance the immune system, reduce the risk of chronic diseases, and increase energy levels Regular workouts are known to improve muscle strength and flexibility, which can prevent injuries and enhance mobility. Moreover, exercise contributes to better sleep and improved mood, which are crucial for daily functioning -------------------------------------------------- Chunk 2: Physical activity can also help reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, leading to a more balanced emotional state Activities like walking, jogging, or swimming can be easily incorporated into a daily routine, making it accessible for everyone By setting realistic goals and staying consistent, individuals can enjoy these benefits and lead a healthier lifestyle -------------------------------------------------- Chunk 3: Group fitness classes or sports teams can provide motivation and social support, making exercise more enjoyable and sustainable --------------------------------------------------

Now that we've gone through an implementation of our three semantic chunking methods, we'll run some experiments so we can compare them more systematically - using two popular benchmark datasets, a specific embedding model, and a reranker.

Datasets

HotpotQA is a good test of our methods in handling complex, multi-hop reasoning tasks, while SQUAD is good at evaluating our methods on their ability to identify and extract the exact span of text that answers a given question.

Embedding models

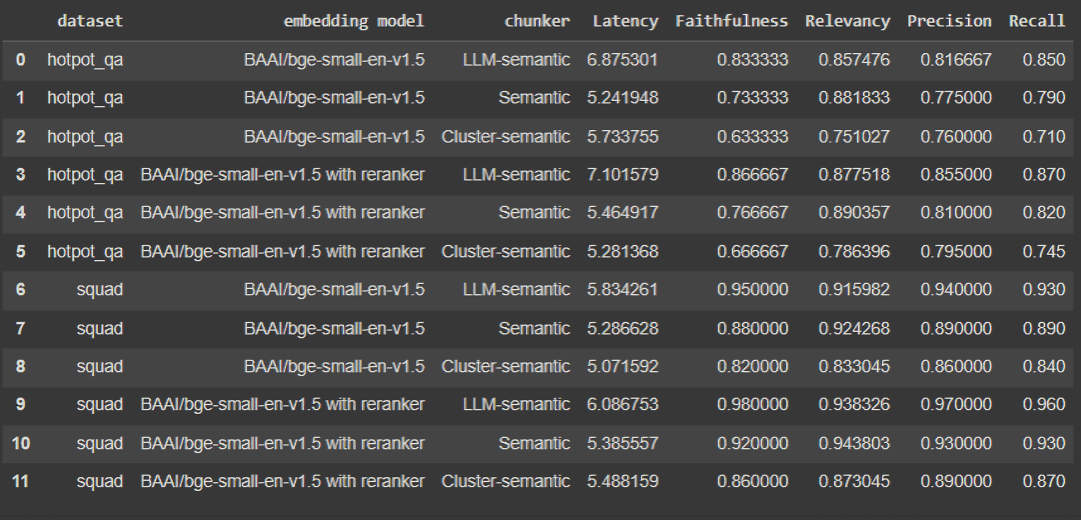

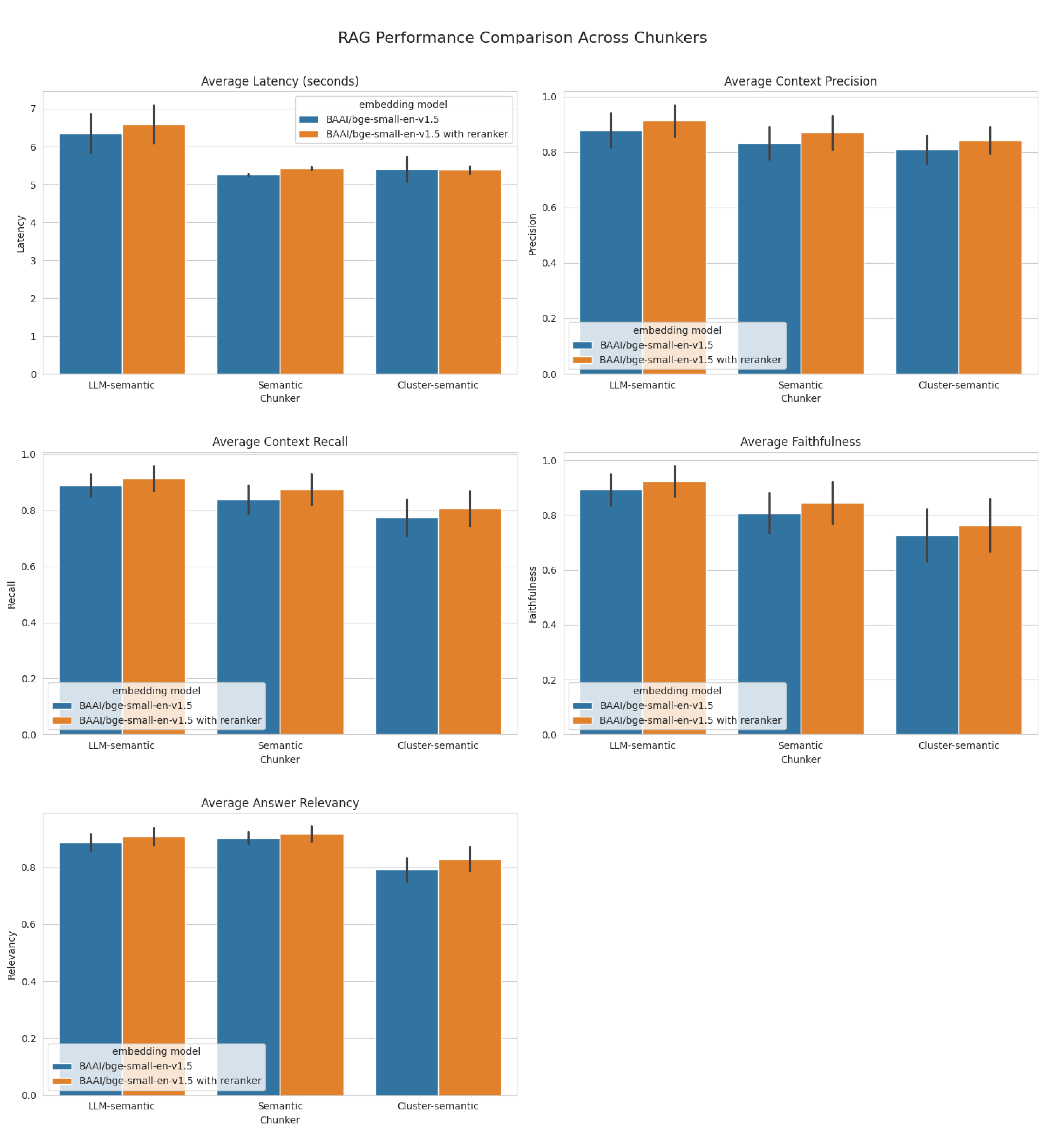

After running our experiments, we evaluated our three methods - embedding-similarity-based, hierarchical-clustering-based, and LLM-based chunking - in terms of latency, context precision, context recall, faithfulness, and relevancy.

Let's visualize these results side by side on a graph.

Stay updated with VectorHub

Continue Reading